The ketogenic diet has built a powerful reputation as a fast, effective way to lose weight. By slashing carbohydrates and loading up on fats, keto promises to push the body into a metabolic state where fat—not sugar—becomes the primary fuel. For many people, the results on the scale can be dramatic.

But new research suggests that what looks like success from the outside may mask deeper metabolic problems underneath.

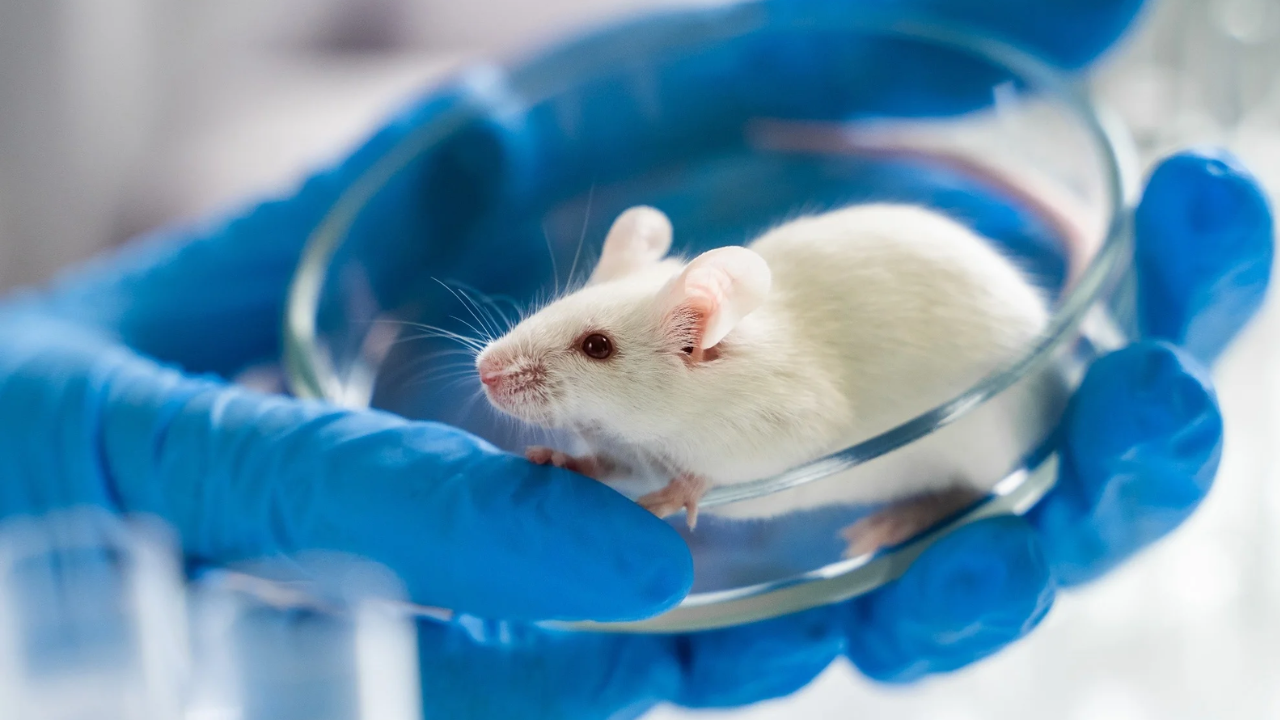

A long-term mouse study has found that a keto-style diet can stress key organs involved in metabolism—particularly the liver and pancreas—raising fresh questions about the safety of prolonged, extreme carbohydrate restriction.

What the New Study Looked At

Researchers at the University of Utah followed groups of mice for at least nine months, a significant stretch in a rodent’s lifespan and long enough to observe long-term metabolic effects rather than short-lived changes.

The mice were fed one of four carefully designed diets:

- A high-fat Western-style diet

- A very-high-fat, very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic-style diet

- A low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet

- A low-fat diet with extra protein, matched to the protein level of the keto group

The ketogenic diet was formulated to closely resemble how humans typically follow keto: extremely low in carbohydrates, very high in fat, and moderate in protein.

At first glance, the results appeared encouraging for keto fans.

The Superficial Win: Less Weight Gain

Compared with mice on the standard Western high-fat diet, mice on the keto-style diet gained less weight. This aligns with what many people experience when starting keto: weight loss or reduced weight gain relative to high-carb, ultra-processed diets.

If weight were the only metric that mattered, the story might end there.

But when researchers looked deeper—inside the organs that regulate fat and sugar metabolism—a far more troubling picture emerged.

Fatty Liver Disease in Keto-Fed Mice

Male mice on the ketogenic-style diet developed signs consistent with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

This happens when excess fat accumulates inside liver cells. Over time, fatty liver can impair the liver’s ability to:

- Regulate blood sugar

- Process fats

- Filter toxins

- Coordinate metabolic signals throughout the body

The core issue, researchers suggest, is fat overload. When dietary fat intake is pushed extremely high, the body must store or process that fat somewhere. In these mice, much of it ended up in the liver.

Fatty liver disease is already common in humans, particularly among people with obesity, insulin resistance, or type 2 diabetes. Seeing a similar pattern emerge in mice on a long-term ketogenic diet raises concerns that extreme fat intake may worsen—or trigger—this condition under certain circumstances.

Blood Sugar Control: Lower, But Not Healthier

Perhaps more surprising were the changes in blood sugar regulation.

Both male and female mice on the keto-style diet showed lower blood glucose and insulin levels within two to three months. At first glance, that sounds beneficial—lower blood sugar and insulin are often cited as keto’s major advantages.

But the mechanism mattered.

Rather than reflecting smooth, efficient glucose control, the low insulin levels appeared to result from impaired insulin production. Pancreatic cells responsible for releasing insulin showed signs of stress and dysfunction.

In simple terms, blood sugar was lower not because the system was working better—but because the pancreas wasn’t responding normally.

Why Pancreatic Stress Is a Red Flag

Insulin is essential for life. It allows cells to absorb glucose from the bloodstream and use it for energy. When insulin production falters, blood sugar regulation becomes unstable.

The researchers suspect that constant exposure to high levels of fatty acids may strain the pancreas over time, reducing its ability to release insulin appropriately. While this effect was observed in mice, it raises a worrying possibility: prolonged keto dieting could, in some cases, increase the risk of metabolic dysfunction rather than prevent it.

Ironically, a diet often promoted as protective against type 2 diabetes may, under certain conditions, push metabolic systems in the opposite direction.

A Crucial Detail: Some Effects Were Reversible

There was one reassuring finding.

When mice were taken off the ketogenic diet, their metabolic markers began to improve. Blood sugar regulation recovered, and insulin production showed signs of returning toward normal.

This suggests that at least part of the metabolic stress caused by prolonged ketosis may be reversible, provided the diet is not maintained indefinitely.

However, how quickly—or completely—such recovery would occur in humans remains unknown. Human metabolic systems are more complex, and people often follow keto intermittently or cycle in and out of it, rather than stopping abruptly under controlled conditions.

What This Study Does—and Does Not—Prove

It’s critical to emphasize that this research was conducted in mice, not humans.

Mice are widely used in metabolic research because they share many biological pathways with humans. However, there are important differences:

- Mice have shorter lifespans

- Their diets are tightly controlled

- Their metabolic responses can be more extreme

This study does not prove that people following a ketogenic diet will inevitably develop fatty liver disease or pancreatic dysfunction.

What it does show is that the biological mechanisms underlying keto are not universally benign, especially when sustained long term. It challenges the idea that weight loss alone is a sufficient marker of metabolic health.

Why Keto Exists in the First Place

The ketogenic diet was not invented as a weight-loss trend.

It originated nearly a century ago as a medical therapy for epilepsy, particularly in children whose seizures did not respond to medication. By mimicking the biochemical state of fasting, keto was shown to significantly reduce seizure frequency in some patients.

In medical settings, ketogenic diets are typically:

- Closely supervised

- Accompanied by regular blood tests

- Adjusted based on individual response

In those cases, potential side effects are weighed against the benefit of controlling severe neurological disease.

The modern popularity of keto as a DIY weight-loss strategy is a very different context—often involving minimal medical oversight and long-term adherence driven by online advice.

Why Short-Term Success Can Be Misleading

Many keto studies in humans focus on short-term outcomes—weeks or months rather than years. These studies often show:

- Rapid weight loss

- Reduced appetite

- Lower fasting glucose

But fewer studies examine what happens to:

- Liver fat

- Pancreatic function

- Lipid balance

- Long-term insulin responsiveness

The mouse data suggest that focusing only on the scale may hide emerging problems that take longer to appear.

Practical Takeaways for People Considering Keto

This study doesn’t mean everyone should avoid ketogenic diets entirely. It does suggest that long-term, extreme versions of keto deserve caution.

If someone is considering or already following a strict ketogenic diet for months at a time, sensible steps may include:

- Consulting a healthcare professional, especially with a history of liver disease or diabetes

- Monitoring liver enzymes and blood lipids

- Tracking long-term blood sugar markers like HbA1c

- Emphasizing unsaturated fats (olive oil, nuts, fish) over butter and processed meats

- Limiting alcohol, which further strains the liver

For many people, a moderate low-carb approach—cutting refined carbohydrates and ultra-processed foods without pushing fat intake to extremes—may deliver meaningful benefits with fewer risks.

Key Concepts Explained Simply

| Term | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Ketosis | A metabolic state where the body burns fat and produces ketones instead of relying on glucose |

| Fatty liver disease | Accumulation of fat in liver cells, which can impair liver function |

| Insulin | A hormone that allows cells to absorb glucose from the blood |

| Metabolic health | The combined functioning of systems controlling blood sugar, fats, blood pressure, and weight |

How This Could Play Out in Real Life

Imagine two people start keto at the same time. Both lose weight quickly. Both see lower blood sugar readings.

One checks blood work regularly and notices rising liver enzymes and triglycerides. The other doesn’t test anything and assumes everything is fine because the scale keeps dropping.

The mouse study suggests the first person has early warning signs—signals that could prompt dietary adjustment before lasting harm occurs.

Weight loss stories often end with a number. Biology doesn’t.

The Bigger Message

This research adds to a growing body of evidence that how weight is lost matters as much as how much is lost. Diets that deliver rapid results may still carry hidden trade-offs, especially when followed rigidly for long periods.

The ketogenic diet remains a powerful metabolic tool—but like any powerful tool, it works best when used carefully, with awareness of its limits.

The scale can be persuasive. The liver and pancreas, however, keep their own score.