Far offshore, where the Pacific turns steel-grey and the horizon feels endlessly distant, marine biologists are trained to expect the unexpected. Even so, the bird that slid into view off central California recently left seasoned observers momentarily stunned.

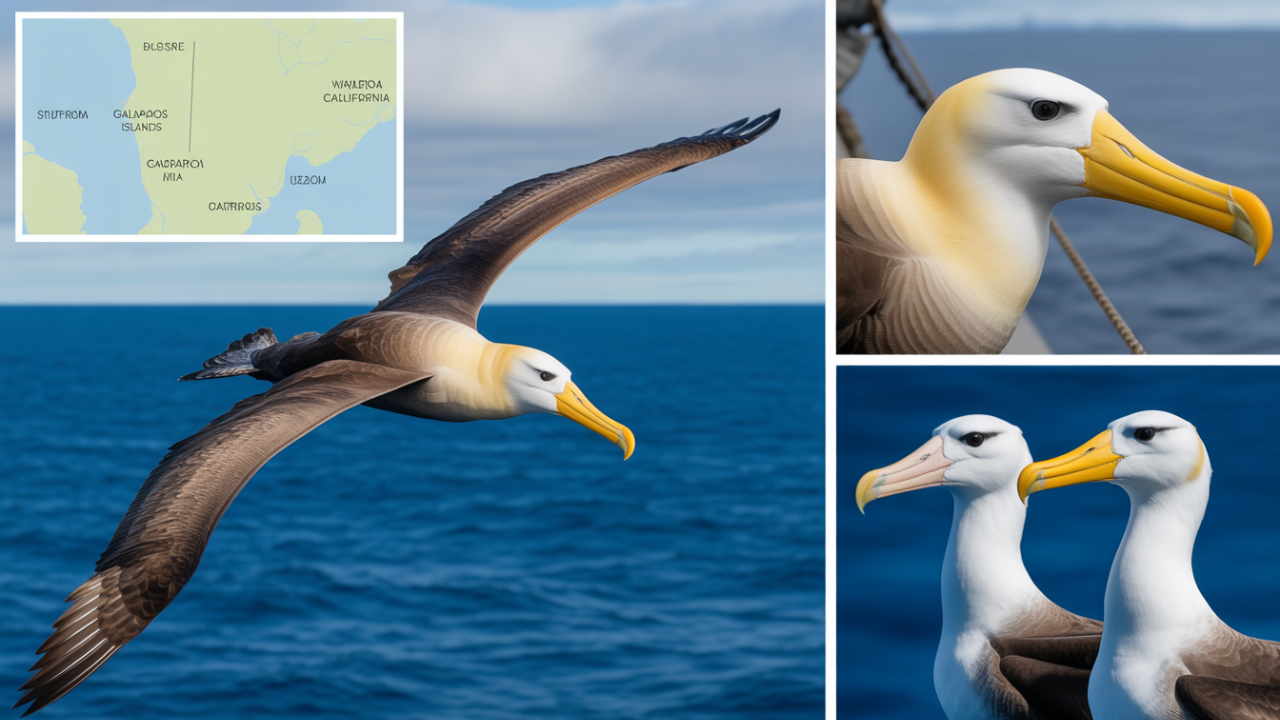

Gliding low over the waves was a waved albatross — a species that almost never ventures far from the equatorial waters around the Galapagos Islands. Yet here it was, roughly 3,000 miles north of its normal home, cruising the temperate Pacific like it belonged.

For conservation scientists, birders and climate researchers alike, the sighting raises a deceptively simple question with complex implications: how did a critically endangered tropical seabird end up off California — and what does it mean?

A visitor that shouldn’t be there

The bird was spotted about 23 miles (37 kilometres) off Point Piedras Blancas, midway between San Francisco and Los Angeles. That location alone makes the encounter extraordinary. Waved albatrosses are considered tropical specialists, rarely leaving waters near the equator.

This observation marked only the second documented record north of Central America. An earlier sighting off Sonoma and Marin counties the previous October is now believed to have involved the same individual, suggesting the bird lingered along the California coast for months.

For a species whose global population breeds almost entirely on one small island, this kind of detour is almost unheard of.

A giant of the Galapagos skies

With a wingspan reaching 8 feet (2.4 metres), the waved albatross is the largest breeding bird in the Galapagos. Its pale yellow bill, soft brown plumage and dark, expressive eyes make it unmistakable once you know what you are looking at.

Yet seeing one outside its normal range can still feel unreal.

Marine ornithologist Tammy Russell, a contract scientist with the Farallon Institute and a postdoctoral scholar at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, described the moment simply: shock.

At first glance, the bird looked like a familiar North Pacific albatross. Then the details clicked — the bill shape, the colour, the flight style. This was something else entirely.

A species tied to one place

Unlike many albatrosses that roam entire ocean basins, the waved albatross has an unusually restricted life cycle.

- Breeding: Almost the entire population nests on Española Island, with a tiny secondary colony on Isla de la Plata.

- Foraging: Most feeding occurs in the tropical eastern Pacific, particularly along nutrient-rich waters influenced by the Humboldt Current.

- Movement: While capable of immense journeys, the species usually stays within warm equatorial latitudes.

That tight geographic focus is one reason the species is so vulnerable — and why a California appearance stands out so sharply.

Storms, wandering instincts, or something else?

So how does a Galapagos breeder end up off California?

Scientists stress there is no single clear explanation, but several plausible scenarios.

1. Pushed by weather

Strong storm systems and unusual wind patterns can displace seabirds over vast distances. Once caught in a powerful atmospheric flow, a bird may simply go with it — especially one built for long-distance gliding.

2. A natural “vagrant”

Some individuals are natural roamers. Ornithologists call them vagrants — animals that wander far beyond the typical range of their species. These individuals are rare but well documented across bird groups.

Marshall Iliff, project leader at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, notes that seabirds routinely cover enormous distances in search of food. In his view, a single albatross this far north is most likely an anomaly rather than evidence of a shifting population.

3. A “gap year” from breeding

Waved albatrosses typically lay one egg per year, with chicks fledging around January. Adults that skip a breeding season may have unusual freedom to roam.

Given that these birds can live 40–45 years, a non-breeding year offers a rare chance to explore far beyond familiar waters.

Why this matters for conservation

The waved albatross is listed as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Its population is small, slow-breeding and tightly clustered in one region.

Key threats include:

- Accidental capture on longline fishing gear

- Declining prey availability from overfishing

- Habitat disturbance on nesting islands

- Climate-driven changes in ocean temperature and currents

Because the species is so geographically constrained, even small environmental changes can have outsized effects. That’s why sightings far outside its known range immediately catch scientific attention.

One bird does not make a trend — but it sets a baseline

Russell and her colleagues are careful not to overinterpret a single sighting. One albatross, even an extraordinary one, does not prove a shift in species behaviour.

However, it does create a baseline.

Russell points out that other seabirds tell a cautionary story. Several booby species that were once rare off California are now regular visitors, a change linked to warming waters and repeated marine heatwaves.

If more waved albatrosses begin appearing in temperate waters, scientists would need to ask deeper questions about:

- food availability near the Galapagos

- changes in wind and current patterns

- increasing frequency of extreme climate events

For now, this bird is best understood as an outlier — but an important one.

Built for epic journeys

What makes such a detour physically possible is the albatross’s remarkable flight technique.

Like its relatives, the waved albatross uses dynamic soaring. By repeatedly climbing into stronger winds and descending into calmer air, it extracts energy from the atmosphere itself, allowing it to travel vast distances with minimal effort.

This strategy explains how an animal weighing just a few kilograms can cross oceans — and why a 3,000-mile journey, while extraordinary, is not impossible.

| Species | Typical range | Wingspan |

|---|---|---|

| Waved albatross | Tropical eastern Pacific | Up to 2.4 m (8 ft) |

| Black-footed albatross | North Pacific, California coast | Up to 2.1 m |

| Laysan albatross | North Pacific, Hawaii | Up to 2.1 m |

Unlike the black-footed and Laysan albatrosses that regularly patrol California waters, the waved albatross normally avoids cooler seas — making this encounter especially striking.

A moment for birders, a signal for scientists

For pelagic birdwatchers, seeing a waved albatross off California is a once-in-a-lifetime experience. Such sightings instantly become legendary within the birding community.

For scientists, the meaning is quieter but deeper. The Pacific Ocean is changing rapidly. Species distributions are shifting, sometimes subtly, sometimes abruptly. Extreme wanderers like this albatross can act as early indicators — not proof, but hints.

Two concepts matter here:

- Vagrancy: a rare individual far outside its normal range

- Baseline: the reference point for detecting future change

This bird is both.

If future surveys record more waved albatrosses in northern waters, researchers could combine sightings with satellite data, fisheries records and climate models to test whether environmental pressures are nudging the species beyond its historic limits.

A question carried on the wind

For now, the lone albatross off California remains an enigma — a tropical giant gliding through cooler seas, defying expectations and reminding us how fluid the natural world can be.

Whether it was driven by storms, curiosity, hunger or chance, its presence forces scientists to look twice at the map. Sometimes, the most important signals of change arrive quietly, on wings that were never supposed to be there.