Your alarm rings. For some people, it feels almost gentle—a nudge that fits naturally into the body’s rhythm. For others, it lands like an insult, cutting short a night that never quite felt finished. Same clock. Same hour. Completely different physical reactions.

For decades, the early bird versus night owl debate has been treated as a matter of personality, productivity, or moral virtue. Early risers were disciplined. Night owls were creative but unreliable. Now science is shifting the conversation in a more uncomfortable direction.

It turns out this argument isn’t really about habits or willpower. It’s about biology. And new research suggests that who pays the bigger health price may depend less on how much you sleep, and more on when you sleep—and whether your life allows your internal clock to do its job.

What researchers are actually studying when they talk about larks and owls

Scientists use the term chronotype to describe a person’s natural timing preference. It reflects when your body wants to sleep, wake, eat, and be active—not what your job or family schedule demands.

Chronotype is shaped by:

- Genetics

- Age

- Light exposure

- Hormonal timing

It isn’t just a lifestyle choice. It’s built into your physiology.

Broadly, people fall into three groups:

- Larks (morning types)

Wake easily, feel sharp early in the day, get sleepy earlier in the evening. - Owls (evening types)

Struggle with early mornings, peak mentally later in the day or at night, naturally go to bed late. - Intermediate types

Sit somewhere in the middle and adapt more easily.

Chronotype also changes with age. Teenagers skew strongly owl-like. Middle age pulls people earlier. Many older adults wake very early without trying.

The problem begins when biology and daily life stop lining up.

Circadian rhythm: the invisible system running your body

Behind chronotype sits a deeper system: your circadian rhythm. This is your body’s internal 24-hour clock, controlling far more than sleep.

It regulates:

- Hormone release (melatonin, cortisol, insulin)

- Body temperature

- Blood pressure

- Digestion

- Alertness and reaction time

Light is its strongest signal. Morning daylight tells the brain, this is daytime. Darkness tells it to prepare for rest.

When your schedule matches this rhythm, your systems work efficiently. When it doesn’t, scientists call it circadian misalignment.

And that’s where health problems start to accumulate.

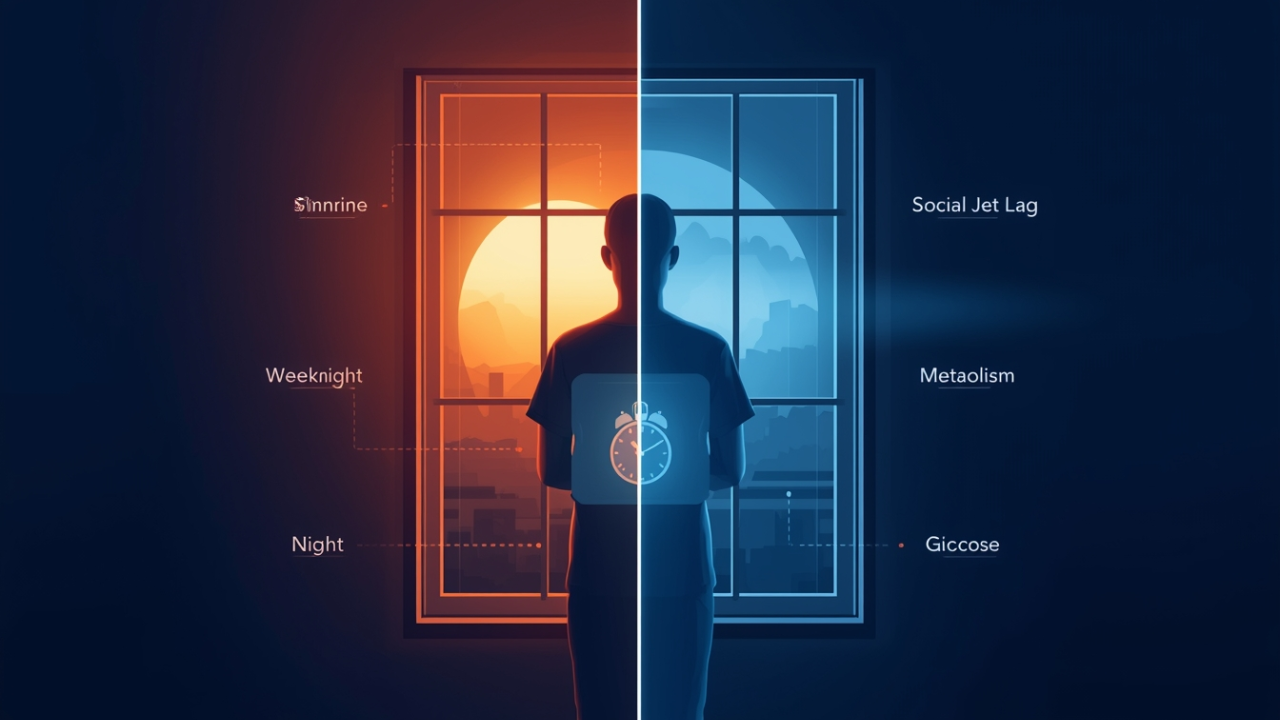

The real issue isn’t being a night owl—it’s social jet lag

Night owls are often painted as unhealthy by default. That’s misleading.

The real danger is social jet lag: the constant mismatch between your biological clock and your social obligations.

Classic example:

- You naturally fall asleep around 1:30 am.

- Work forces you to wake at 6:30 am.

- You try to “catch up” by sleeping late on weekends.

Your body never settles into a stable rhythm. It’s like flying across time zones twice a week, every week, without leaving home.

Research published in leading cardiovascular journals shows that people with strong evening chronotypes are far more likely to live in this state of chronic misalignment.

How chronic misalignment affects the body

When your internal clock is constantly overridden, multiple systems start to strain—not dramatically at first, but quietly and persistently.

Cardiovascular system

- Higher average blood pressure

- Less healthy daily heart-rate patterns

- Increased strain on blood vessels

Metabolic system

- Poorer blood sugar control

- Increased insulin resistance

- Greater risk of type 2 diabetes

Hormonal balance

- Disrupted melatonin production

- Elevated evening cortisol (stress hormone)

- Reduced sleep quality even when time in bed is long

Behavioural side effects

- More late-night snacking

- Irregular meal timing

- Less consistent physical activity

These factors tend to cluster, meaning one problem amplifies another.

Why studies keep pointing the finger at owls

Large population studies consistently find that people with strong evening chronotypes show higher rates of cardiometabolic risk factors—but only when they are forced into early schedules.

Observed associations include:

- Higher rates of obesity, especially abdominal fat

- Greater likelihood of prediabetes or diabetes

- Less favourable cholesterol profiles

- Higher smoking and alcohol use in some groups

Timing plays a role here too. Late eaters consume calories when the body is least prepared to process glucose and fat efficiently. The same meal eaten at 7 pm and 11 pm is not metabolically identical.

Why morning types often come out ahead

Morning types tend to live in better alignment with modern social structures. That alignment itself appears protective.

Larks are more likely to:

- Maintain stable sleep and wake times

- Get natural morning light exposure

- Eat earlier, more evenly distributed meals

- Be active during daylight hours

This doesn’t make early risers morally superior or biologically perfect. It simply means their lifestyle reinforces their internal clock instead of fighting it.

Should night owls force themselves to wake up earlier?

This is where many people go wrong.

Forcing an owl to wake early without adjusting bedtime, light exposure, or evening habits often leads to chronic sleep deprivation—not better health.

The goal isn’t a heroic 5 am alarm. It’s reducing the daily tug-of-war between biology and obligation.

Health improves when misalignment shrinks, not when suffering increases.

Practical ways night owls can reduce health risk

If you naturally lean late, the science doesn’t say “give up and accept the damage”. It suggests small, consistent shifts.

1. Move bedtime gradually

Advance sleep time by 15–20 minutes every few nights. Abrupt changes usually fail.

2. Use morning light strategically

Bright light within an hour of waking—outdoors if possible—signals your brain to shift earlier.

3. Tame evening light

Limit bright screens late at night. Blue light tells your brain it’s still daytime.

4. Eat earlier, lighter dinners

Finish your main meal at least three hours before sleep. Keep late snacks small and low-sugar.

5. Stabilise wake-up times

Huge weekend sleep-ins worsen social jet lag. A one-hour difference is far better than three.

None of these require becoming a morning person. They simply help your clock stop fighting itself.

What doctors are starting to notice

In cardiology and metabolic clinics, timing is gaining attention alongside diet and exercise.

When patients present with:

- Obesity

- Prediabetes

- High blood pressure

Doctors increasingly ask about:

- Bedtime and wake-up patterns

- Weekend sleep shifts

- Late-night eating habits

Some research settings use wearable devices to track sleep timing, activity, and light exposure. The patterns often reveal more than a single blood test.

Two identical lives, two very different outcomes

Imagine two people with the same job, income, and diet.

Person A (lark):

- Wakes at 6:30 am naturally

- Eats breakfast early

- Exercises after work

- In bed by 10:30 pm

Person B (owl):

- Naturally sleepy at 1:30 am

- Forced to wake at 6:30 am

- Skips breakfast

- Eats late, scrolls at night

- Sleeps in heavily on weekends

On paper, both “sleep about seven hours”. In reality, one body runs smoothly. The other is constantly adjusting, compensating, and paying a metabolic tax.

Over years, that difference matters.

So… who really pays the health price?

The evidence points to a clear conclusion:

- Early risers don’t win because early is better.

- They win because alignment is better.

Night owls who can live on owl-friendly schedules—later work hours, consistent sleep timing—often show far fewer health penalties. The real danger zone is being biologically late in a socially early world.

What this means for you

If you wake early and feel good, protect that rhythm. It’s working in your favour.

If you’re an owl, the message isn’t panic—it’s strategy. Respect your biology while gently reducing misalignment. Pay closer attention to heart and metabolic markers. Treat sleep timing as part of your health plan, not a moral failing.

The real question isn’t “early or late?”

It’s: how well does your life fit your internal clock?

The closer the match, the lower the price your body has to pay.

Key takeaways

| Insight | What it means |

|---|---|

| Chronotype is biological | You don’t choose lark or owl |

| Misalignment drives risk | Not late nights alone, but forced schedules |

| Morning types align more easily | Social structure favours them |

| Small timing shifts help | Gradual change beats brute force |

| Health isn’t just “how much sleep” | Timing matters |